摘要

鈣是一種重要的礦物質,在人體健康,特別是骨骼健康中扮演著不可或缺的角色。海洋生物鈣是一種豐富的資源,其結構活性複雜且被廣泛接受。這篇綜述評估了海洋生物鈣在來源、鈣補充劑的使用、鈣的生物利用率以及海洋鈣的新應用方面的研究進展。同時,也探討了在生物醫學研究、製藥、保健和食品工業中融入海洋生物鈣產品的未來發展潛力。本綜述旨在提供有關海洋生物資源利用和產品開發的全面文獻記錄。

主題關鍵詞:營養學、天然產品

引言

鈣是一種重要的微量營養素,廣泛被認為影響骨骼健康和人體代謝。缺鈣可能引發骨質疏鬆、佝僂病、癲癇和貧血等問題。鈣通過食物或鈣補充劑進入循環系統,並在血液和骨骼鈣之間保持動態平衡【1】。鈣的主要來源是乳製品,包括牛奶及其副產品,如奶酪和煉乳,其次是穀物和豆腐等其他來源【2】。然而,不適當的飲食可能會降低鈣的生物利用率。例如,穀物中的植酸和綠葉蔬菜中的草酸可能導致鈣沉澱為植酸鈣和草酸鈣,這些是不溶性化合物【3】。在美國的一項研究發現,僅靠食物攝取礦物質和維生素的成年人中,約有 38% 的人鈣攝取不足,約 93% 的人維生素 D 攝取不足,而維生素 D 在鈣吸收率、骨骼恆定和骨修復中起關鍵作用【4】【5】。隨著年齡增長,缺鈣的情況逐漸惡化【6】。慢性缺鈣導致骨質疏鬆成為一種流行病【7】。越來越多的人面臨缺鈣及其相關疾病【8–10】。因此,越來越多的人根據醫生或媒體的建議,通過補充劑來增加鈣的攝取【11】。

這些補充劑的鈣來源包括碳酸鈣礦石、富含鈣的動物骨骼、海洋貝殼和甲殼類生物【12】。然而,天然碳酸鈣礦石可能含有有害元素,如重金屬【13】。動物骨骼則可能有傳播朊病毒的風險【14】【15】。近年來,由於其豐富的儲量、高安全性和生物活性,來自海洋的鈣補充劑越來越受到關注【16】【17】。隨著海洋資源的開發和利用,超過 50% 的漁業副產品(包括骨骼、魚鰭、魚頭和內臟)每年作為廢料被丟棄,而這些可以被有效利用。海洋礦物補充劑可能增加骨骼周轉率,有助於防止損傷並修復受損骨骼【18】。作為鈣的重要來源,使用海洋生物鈣是一種提高生物資源利用率的重要方式。本綜述全面評估了海洋鈣的來源、鈣補充劑製備的技術、海洋鈣的生物活性和生物利用率,為開發利用海洋鈣補充劑提供參考。

海洋鈣的來源

海洋中富含生物資源,而鈣是海洋生物的重要礦物成分。來自海洋的鈣主要來源於魚骨、貝類和甲殼類生物的外殼、珊瑚以及海藻(如圖 1 所示)。

來自魚骨的鈣

魚骨是指魚體中的軸骨、附肢骨和魚骨,約占魚體總重的 10–15%【19】。魚骨組織主要由有機的細胞外基質構成,並覆蓋著羥基磷灰石 [Ca₅(PO₄)₃OH]。相比於其他八種魚類,三文魚科魚類的鈣含量最低,而無脂乾物質中的鈣含量可高達 135–147 g/kg【20】。鯊魚軟骨是另一個重要的鈣來源。例如,膠鯊的下顎軟骨中的鈣主要以羥基磷酸鈣晶體 [Ca₁₀(PO₄)₆(OH)₂] 的形式存在,其鈣磷酸鹽含量在乾重基礎上可達 67%,範圍介於 124–258 g/kg【21】。大型魚類的魚骨需經化學和生物方法處理以破壞有機材料,或與膠原蛋白結合以提高鈣的溶解率,因為羥基磷灰石形式的鈣不易被人體吸收【22】。小型魚類如鳳尾魚和鱗鰭魚,其骨骼較柔軟,可製成即食食品,連同骨頭一起食用【23】。魚骨鈣的製備通常包括通過烹煮去除蛋白質和脂肪,使用鹼性和有機溶劑或酵素水解處理,並進行超細粉碎以獲得魚骨粉。

來自貝殼的鈣

貝殼約占貝類總質量的 60%,其碳酸鈣含量可高達 95%。貝殼是高品質海洋鈣的重要來源。貝類養殖為人類提供了一種低環境影響的可持續蛋白質來源【24】。2016 年,全球養殖貝類達到 1713.9 萬噸,占總漁業產量的 21.42%【25】。此外,由於貝殼中的鈣含量高於魚骨,其鈣的產量更大【26】【27】。研究了來自巨扇貝殼粉和化石貝殼粉的鈣補充劑的效果,結果表明這些天然鈣來源具有良好的溶解性和生物利用率【28】。貝殼鈣補充劑已在多個國家銷售,但貝殼資源的利用率仍然很低,其綜合開發和利用需要進一步支持。

來自甲殼類的鈣

人們可以通過食用小型乾蝦或螃蟹直接攝取鈣。甲殼類的加工和消費會產生 30–40% 的海洋資源廢料【29】。甲殼類主要由碳酸鈣 (CaCO₃)、幾丁質和蛋白質組成【30】。對蝦和蟹殼的研究主要集中於幾丁質和蛋白質資源的利用,而鈣有時作為副產品回收,例如氫磷酸鈣、乳酸鈣和鈣【31】。

來自珊瑚的鈣

珊瑚鈣來自多種生物的外骨骼。珊瑚鈣是一種天然的海洋鈣來源,含有 24% 的鈣、12% 的鎂以及超過 70 種礦物質。近年來,珊瑚鈣作為一種補鈣新趨勢,常被用於治療骨代謝紊亂、骨質疏鬆及其他骨骼疾病【33】【34】。

來自海藻的鈣

海藻,尤其是綠藻,富含多種礦物質,如鈣【35】。例如,Aquamin 是一種典型的富鈣補充劑,來自紅海藻 Lithothamnion 的鈣化骨骼遺骸,其鈣含量高達 31%【36】。一項研究表明,與碳酸鈣補充劑相比,海藻鈣對馬匹的鈣吸收效果更好【37】。研究還發現,從海藻提取的鈣在骨骼鈣化中具有有益的促進作用,尤其是在骨質疏鬆的動物模型中【38】。由牡蠣殼粉和海藻製備的藻鈣,其生物利用率高於碳酸鈣【39】。

鈣補充劑與生物利用率

直接攝取海洋來源的鈣

最常見的直接鈣補充劑包括小乾蝦、貝殼粉和小型魚類。若干海洋鈣補充劑(如牡蠣殼和珊瑚鈣)已在不同國家商業化。然而,來自這些海洋來源的主要成分是碳酸鈣和多羥基磷酸鈣,這些成分難以吸收且會增加胃部負擔【40】。為了提高鈣的吸收率,通常需要先將海洋來源粉碎或進行真空加熱處理【41】【42】。

研究發現,與碳酸鈣補充劑或其他富鈣食物相比,海洋來源的鈣具有一定優勢。例如,Aquamin 的生物利用率更高,且在減緩骨質流失方面優於碳酸鈣【36】。此外,魚骨粉 (Phoscalim) 和魟魚軟骨水解物 (Glycollagene) 在短期鈣吸收和骨吸收方面與牛奶相當【16】。用鱈魚骨製成的鈣片足以作為鈣補充劑並預防骨質疏鬆【43】。

目前,國際推薦的一般人群每日鈣攝取量為 700–1200 毫克。然而,青少年(9–18 歲)需要約 1300 毫克鈣,而低鈣飲食的孕婦則需要 1500–2000 毫克鈣【44】【45】。研究顯示,缺鈣人群中超過 50% 為 70 歲以上的男性和女性、51–70 歲的女性、9–13 歲的男孩和女孩,以及 14–18 歲的女孩【46】。意識性地補充海洋鈣對預防缺鈣非常有效,但直接從海洋生物中攝取鈣不足以治療缺鈣疾病。治療缺鈣疾病還需要選擇更高劑量的鈣補充劑或藥物【5】。

有機酸鈣

有機酸鈣(例如檸檬酸鈣、乳酸鈣、葡萄糖酸鈣、醋酸鈣、甲酸鈣和丙酸鈣)具有更高的生物利用率、溶解性和吸收率,無論胃內容物如何,因為它們對胃 pH 值的敏感性低於碳酸鈣【11】【40】【47】。有機酸鈣主要通過鈣化合物的中和或發酵製備而成(圖 2)。作為一種膳食鈣補充劑,甲酸鈣被發現比碳酸鈣和檸檬酸鈣具有顯著的優勢【48】。葡萄糖酸鈣被證明具有較高的相對生物利用率,並且比碳酸鈣更容易被人體耐受【49】。

然而,葡萄糖酸鈣和乳酸鈣的鈣濃度較低,因此作為口服補充劑並不實用。醋酸鈣和丙酸鈣也不廣泛使用【50】。單獨使用有機酸鈣對吸收效果並不理想,因為它們可能與食物中的草酸或植酸結合。將鈣與兩種或更多的有機酸結合,例如檸檬酸蘋果酸鈣 (CCM)【10】,或與牛膠原蛋白肽結合的檸檬酸鈣【51】【52】,則可以改善吸收效果。此外,聚醣(Polycan)與乳酸–葡萄糖酸鈣的結合使用,被發現相比單獨使用有機酸鈣具有有益的協同作用【53】【54】。

海洋來源的有機酸鈣主要包括魚骨、蝦殼、蟹殼和其他貝殼【3】。為了促進鈣的吸收,應根據營養成分和相關加工特性選擇適當的處理方法,例如焙燒、酵素水解和發酵方法【55】【56】。隨後,加入檸檬酸、葡萄糖酸、乳酸、醋酸和/或丙酸以製備有機酸鈣。經減壓處理後,貝類鈣與檸檬酸和乳酸結合的鈣的溶解性和生物利用率得到了提高【26】。魚骨可以與乳酸乳球菌 (Leuconostoc mesenteroides) 發酵以獲得高含量的可溶性鈣,包括游離鈣、鈣氨基酸、醋酸鈣、小肽鈣和乳酸鈣。草魚骨的發酵不僅可以提高鈣的生物利用率,還能避免魚骨鈣和水產蛋白的浪費【57】。

鈣螯合物

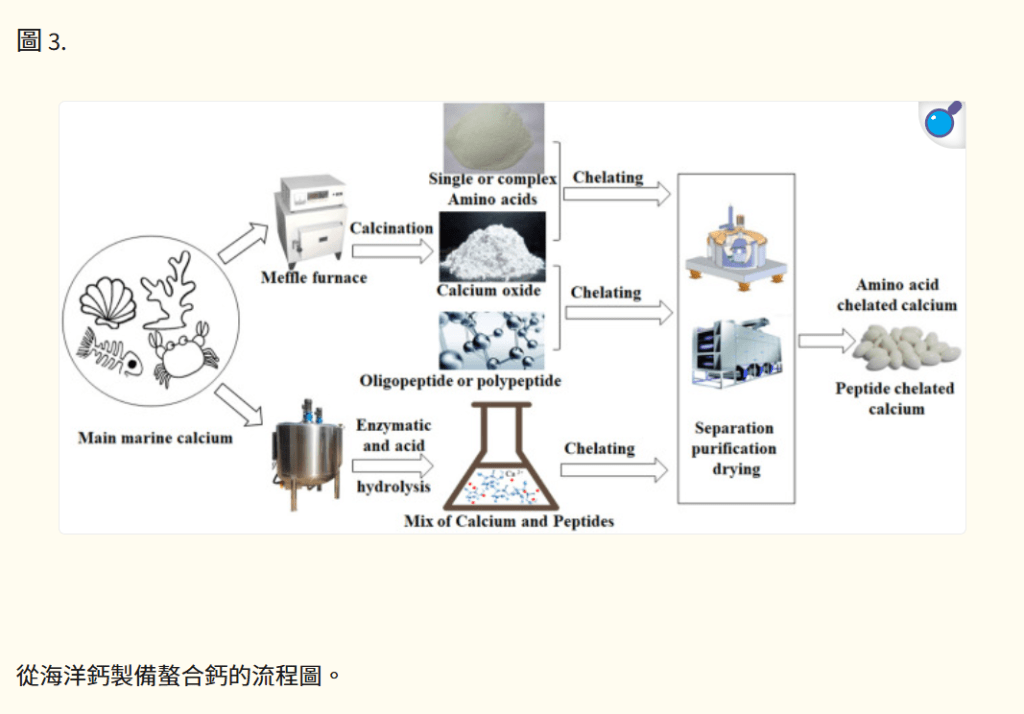

鈣螯合物是指氨基酸或肽與金屬鈣離子之間形成穩定鍵的金屬複合物,包括兩種主要產品:鈣氨基酸螯合物和鈣肽螯合物【58–60】。它主要通過多肽或寡肽與鈣離子螯合,或單一或複合氨基酸與鈣離子螯合製備而成(圖 3)。氨基酸螯合鈣不依賴於維生素 D3,並且可以通過氨基酸代謝被人體吸收。例如,賴氨酸鈣是一種新型的鈣製劑,可能具有更好的吸收效果,使其成為比碳酸鈣和檸檬酸蘋果酸鈣 (CCM) 更好的鈣補充劑【61】。

然而,肽螯合鈣相較於其他鈣補充劑具有更多優勢【62–64】。越來越多的螯合肽被發現能促進和改善礦物質的生物利用率【65】【66】。通過酵素水解將魚骨鈣與具有鈣結合能力的骨膠原肽結合製備的鈣肽螯合物,顯示出顯著的鈣生物利用率提升【67–69】。基於藻類肽的鈣螯合複合物和藻酸鈣納米顆粒被認為具有作為鈣補充劑以改善骨骼健康的潛力【70–72】。

然而,肽螯合鈣的生產成本高,產量低。隨著新型製備技術的發展,肽螯合鈣有可能成為一種優良的鈣補充劑。

海洋來源鈣的其他功能

生物活性

海洋生物鈣除了改善鈣的恆定和骨骼健康外,還具有其他生物功能。例如,研究表明珊瑚鈣能調節血壓並預防結腸癌的轉移【30】【73】【74】。來自螺旋藻(Spirulina platensis,一種藍綠藻)中的螺旋藻鈣螯合物被證明能有效抑制單純皰疹病毒1型 (HSV-1),並可能對其他皰疹病毒感染有抑制作用【75】。珊瑚鈣氫氧化物具有抗氧化作用,在小鼠中可延緩衰老並預防肝臟脂肪變性【76–78】。來自扇貝殼的氧化鈣能抑制假單胞菌(Pseudomonas aeruginosa),該細菌是引起雞蛋腐敗的致病菌,並且對化學試劑(如消毒劑和清潔劑)有很強的抗性【79】。來自牡蠣的鈣在抑制口腔鱗狀細胞癌的形成和增殖方面表現出良好的效果【80】。

新材料

來自海洋的鈣可以作為高附加值化合物的原材料,應用於生物醫學研究、製藥、保健和食品工業【81】。研究表明,牡蠣殼、蛤殼、烏賊骨和鮭魚骨具有生產多孔支架的巨大潛力【82–85】。這些支架的結構特性有助於改善生物活性,包括機械性能、骨組織生長和血管化【86】。從鮭魚骨和虹鱒骨中提取的天然羥基磷灰石 (nHAP) 在骨組織工程中作為骨植入材料替代品展現了巨大潛力【87】。海洋生物鈣還可用於製備吸附材料,在水處理中表現出廣泛的應用潛力。例如,由蟹殼製成的富鈣生物炭可用於去除廢水中的染料和磷【88】【89】。由牡蠣殼合成的不溶性矽酸鈣水合物可用於去除有機污染物和重金屬離子【90】。從大西洋鱈魚骨中提取的單相羥基磷灰石 (HA) 和雙相磷酸鈣 (HA/β-TCP) 無已知的細胞毒性,在模擬體液中顯示出良好的生物活性【91】。因此,從海洋生物提取的磷酸鈣在製備抗細菌感染的骨替代材料或骨缺損修復方面具有良好的前景。從鱈魚骨中提取的羥基磷灰石 (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, HAp) 作為一種鈣磷酸鹽,是防曬配方中更安全的選擇,顯示其在保健品和化妝品中的廣泛應用潛力【92】。

食品添加劑

來自海洋加工廢料的生物鈣仍可用於食品加工。例如,魚骨可以添加到魚糜中以改善產品的凝膠性能【93】。牡蠣殼鈣粉可以提高重組火腿的咀嚼性和彈性【94】。富含鈣的蝦殼和蟹殼也可以用來製備食品絮凝劑【95】。許多食品添加劑含有鈣,例如碳酸鈣、矽酸鈣、硫酸鈣和乳酸鈣。由海洋生物製得的鈣添加劑因其天然來源可能更安全。

結論與未來展望

海洋加工廢料通常被視為無用,但它是一種豐富且低成本的鈣來源。一項研究發現,55 種鈣補充劑品牌可根據其主要成分分為七類,其中三類或更多來自海洋生物,主要包括牡蠣/蛤殼、海藻、鯊魚軟骨和螯合鈣產品(表 1)【10】。此外,來自海洋生物的鈣具有良好的生物利用率和生物功能。重新利用海洋生物的副產品不僅可以增加鈣的附加價值,還能減少環境污染的風險。

在鈣補充劑的開發中,未來的工作應集中於海洋生物中蛋白質、膠原蛋白、幾丁質、鈣及其他營養成分的綜合利用,以及利用特定活性成分來提高鈣的生物利用率。在其他應用方面,研究可能需要關注將海洋鈣轉化為健康食品、新材料或食品添加劑的過程,並將其擴展到商業規模。

參考文獻:

1.Shojaeian Z, Sadeghi R, Latifnejad RR. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation effects on metabolic factors, menstrual cycles and follicular responses in women with polycystic ocvary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Caspian J. Intern. Med. 2019;10:359–369. doi: 10.22088/cjim.10.4.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2.Ong AM, Kang K, Weiler HA, Morin SN. Fermented milk products and bone health in postmenopausal women: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials, prospective cohorts, and case–control studies. Adv. Nutr. 2020;11:251–265. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmz108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3.Kim SK, Ravichandran YD, Kong CS. Applications of calcium and its supplement derived from marine organisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2012;52:469–474. doi: 10.1080/10408391003753910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4.Blumberg JB, Frei BB, Fulgoni VL, Weaver CM, Zeisel SH. Impact of frequency of multi-vitamin/multi-mineral supplement intake on nutritional adequacy and nutrient deficiencies in US adults. Nutrients. 2017;9:849. doi: 10.3390/nu9080849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5.Fischer V, Haffner-Luntzer M, Amling M, Ignatius A. Calcium and vitamin D in bone fracture healing and post-traumatic bone turnover. Eur. Cells Mater. 2018;35:365–385. doi: 10.22203/eCM.v035a25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6.Lee YK, et al. Low calcium and vitamin D intake in Korean women over 50 years of age. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2017;35:522–528. doi: 10.1007/s00774-016-0782-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7.Weaver CM, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Shanahan CJ. Cost-benefit analysis of calcium and vitamin D supplements. Arch. Osteoporos. 2019;14:50. doi: 10.1007/s11657-019-0589-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8.Wilson RL, et al. Reduced dietary calcium and vitamin D results in preterm birth and altered placental morphogenesis in mice during pregnancy. Reprod. Sci. 2020;27:1330–1339. doi: 10.1007/s43032-019-00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9.Kim OH, et al. High-phytate/low-calcium diet is a risk factor for crystal nephropathies, renal phosphate wasting, and bone loss. ELife. 2020;9:e52709. doi: 10.7554/eLife.52709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10.Jarosz M, Rychlik E. P-184-calcium and vitamin D intake and colorectal cancer morbidity rates in Poland. Ann. Oncol. 2019;30:v50. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz155.183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

11.Reid IR, Bristow SM, Bolland MJ. Calcium supplements: Benefits and risks. J. Intern. Med. 2015;278:354–368. doi: 10.1111/joim.12394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12.Kim M. Mercury, cadmium and arsenic contents of calcium dietary supplements. Food Addit. Contam. 2004;21:763–767. doi: 10.1080/02652030410001713861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13.Ross EA, Szabo NJ, Tebbett IR. Lead content of calcium supplements. JAMA. 2000;284:1425–1429. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.11.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14.Kim Y, Rodriguez AE, Nowzari H. The risk of prion infection through bovine grafting materials. Clin. Implant. Dent. R. 2016;18:1095–1102. doi: 10.1111/cid.12391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15.Kim Y, Nowzari H, Rich SK. Risk of prion disease transmission through bovine-derived bone substitutes: A systematic review. Clin. Implant. Dent. R. 2013;15:645–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2011.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16.Lecerf JM, et al. Effects of two marine dietary supplements with high calcium content on calcium metabolism and biochemical marker of bone resorption. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;62:879–884. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17.Flammini L, et al. Hake fish bone as a calcium source for efficient bone mineralization. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016;67:265–273. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2016.1150434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18.Nielsen BD, Cate RE, O Connor-Robison CI. A marine mineral supplement alters markers of bone metabolism in yearling arabians. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2010;30:419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2010.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

19.Pateiro M, et al. Nutritional profiling and the value of processing by-products from gilthead sea bream (Sparus Aurata) Mar. Drugs. 2020;18:101. doi: 10.3390/md18020101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20.Toppe J, Albrektsen S, Hope B, Aksnes A. Chemical composition, mineral content and amino acid and lipid profiles in bones from various fish species. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007;146:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21.Patwardhan UN, Pahuja DN, Samuel AM. Calcium bioavailability: An in vivo assessment. Nutr. Res. 2001;21:667–675. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5317(01)00278-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

22.Edmonds JS, Shibata Y, Lenanton RCJ, Caputi N, Morita M. Elemental composition of jaw cartilage of gummy shark mustelus antarcticus Günther. Sci. Total Environ. 1996;192:151–161. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(96)05311-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

23.Chakraborty P, Sahoo S, Bhattacharyya DK, Ghosh M. Marine lizardfish (Harpadon nehereus) meal concentrate in preparation of ready-to-eat protein and calcium rich extruded snacks. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020;57:338–349. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-04066-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24.Stewart-Sinclair PJ, Last KS, Payne BL, Wilding TA. A global assessment of the vulnerability of shellfish aquaculture to climate change and ocean acidification. Ecol. Evol. 2020;10:3518–3534. doi: 10.1002/ece3.6149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25.FAO . The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018. Rome: FAO; 2018. [Google Scholar]

26.Petenuci ME, et al. Fatty acid concentration, proximate composition, and mineral composition in fishbone flour of Nile Tilapia. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2008;58:87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27.Fujita T, Fukase M, Miyamoto H, Matsumoto T, Ohue T. Increase of bone mineral density by calcium supplement with oyster shell electrolysate. Bone Miner. 1990;11:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(90)90017-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28.Miura T, Takayama Y, Nakano M. Effect of shellfish calcium on the apparent absorption of calcium and bone metabolism in ovariectomized rats. Biosci. Biotech. Bioch. 1999;63:40–45. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29.Kandra P, Challa MM, Jyothi HK. Efficient use of shrimp waste: Present and future trends. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2012;93:17–29. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3651-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30.Gbenebor OP, Adeosun SO, Lawal GI, Jun S. Role of CaCO3 in the physicochemical properties of crustacean-sourced structural polysaccharides. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016;184:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2016.09.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

31.Ding H, Lv L, Wang Z, Liu L. Study on the “glutamic acid-enzymolysis" process for extracting chitin from crab shell waste and its by-product recovery. Appl. Biochem. Biotech. 2020;190:1074–1091. doi: 10.1007/s12010-019-03139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32.Laine J, Labady M, Albornoz A, Yunes S. Porosities and pore sizes in coralline calcium carbonate. Mater. Charact. 2008;59:1522–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.matchar.2007.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

33.Reddy PN, Lakshmana M, Udupa UV. Effect of Praval bhasma (Coral Calx), a natural source of rich calcium on bone mineralization in rats. Pharmacol. Res. 2003;48:593–599. doi: 10.1016/S1043-6618(03)00224-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34.Banu J, et al. Dietary coral calcium and zeolite protects bone in a mouse model for postmenopausal bone loss. Nutr. Res. 2012;32:965–975. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35.Marsham S, Scott GW, Tobin ML. Comparison of nutritive chemistry of a range of temperate seaweeds. Food Chem. 2007;100:1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.11.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

36.Brennan O, et al. A natural, calcium-rich marine multi-mineral complex preserves bone structure, composition and strength in an ovariectomised rat model of osteoporosis. Calcified Tissue Int. 2017;101:445–455. doi: 10.1007/s00223-017-0299-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37.Jacobs R, Gordon M, Jerina M. Feeding a seaweed-derived calcium source versus calcium carbonate on physiological parameters of horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2019;76:83. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2019.03.108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

38.Yamaguchi M, Hachiya S, Hiratuka S, Suzuki T. Effect of marine algae extract on bone calcification in the femoral-metaphyseal tissues of rats: Anabolic effect of sargassum horneri. J. Health Sci. 2001;47:533–538. doi: 10.1248/jhs.47.533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

39.Uenishi K, et al. Fractional absorption of active absorbable algal calcium (AAACA) and calcium carbonate measured by a dual stable-isotope method. Nutrients. 2010;2:752–761. doi: 10.3390/nu2070752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40.Li K, et al. The good, the bad, and the ugly of calcium supplementation: A review of calcium intake on human health. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2018;13:2443–2452. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S157523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41.Fujita T, Ohue T, Fujii Y, Miyauchi A, Takagi Y. Heated oyster shell-seaweed calcium (AAACA) on osteoporosis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1996;58:226–230. doi: 10.1007/BF02508640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42.Tsugawa N, et al. Bioavailability of calcium from calcium carbonate, dl-calcium lactate, l-calcium lactate and powdered oyster shell calcium in vitamin d-deficient or -replete rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1995;18:677–682. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43.Huo J, Deng S, Xie C, Tong G. Preparation and biological efficacy of haddock bone calcium tablets. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limn. 2010;28:371–378. doi: 10.1007/s00343-010-9019-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

44.Vavrusova M, Skibsted LH. Calcium nutrition. Bioavailability and fortification. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014;59:1198–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.04.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

45.Capozzi A, Scambia G, Lello S. Calcium, vitamin D, vitamin K2, and magnesium supplementation and skeletal health. Maturitas. 2020;140:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46.Bailey RL, Picciano MF, et al. Estimation of total usual calcium and vitamin D intakes in the United States. J. Nutr. 2010;140:817–822. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.118539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47.Palermo A, et al. Calcium citrate: From biochemistry and physiology to clinical applications. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Dis. 2019;20:353–364. doi: 10.1007/s11154-019-09520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48.Hanzlik RP, Fowler SC, Fisher DH. Relative bioavailability of calcium from calcium formate, calcium citrate, and calcium carbonate. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005;313:1217–1222. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.081893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49.Wiria M, et al. Relative bioavailability and pharmacokinetic comparison of calcium glucoheptonate with calcium carbonate. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2020;8:e589. doi: 10.1002/prp2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50.Straub DA. Calcium supplementation in clinical practice: A review of forms, doses, and indications. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2007;22:286–296. doi: 10.1177/0115426507022003286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51.Liu J, Wang J, Guo Y. Effect of collagen peptide, alone and in combination with calcium citrate, on bone loss in tail-suspended rats. Molecules. 2020;25:782. doi: 10.3390/molecules25040782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52.Liu J, et al. Combined oral administration of bovine collagen peptides with calcium citrate inhibits bone loss in ovariectomized rats. PLoS One. 2015;10:e135019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53.Choi JS, et al. Effect of polycalcium, a mixture of polycan and calcium lactate-gluconate in a 1:9 weight ratio, on rats with surgery-induced osteoarthritis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015;9:1780–1790. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54.Choi JS, et al. Antiosteoporotic effects of polycan in combination with calcium lactate–gluconate in ovariectomized rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 2014;8:957–967. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55.Wang X, et al. Preparation of cucumber seed peptide-calcium chelate by liquid state fermentation and its characterization. Food Chem. 2017;229:487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.02.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56.Bajaj M, Freiberg A, Winter J, Xu Y, Gallert C. Pilot-scale chitin extraction from shrimp shell waste by deproteination and decalcification with bacterial enrichment cultures. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2015;99:9835–9846. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6841-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57.Tang S, et al. Preparation of a fermentation solution of grass fish bones and its calcium bioavailability in rats. Food Funct. 2018;9:4135–4142. doi: 10.1039/C8FO00674A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58.Wang L, et al. Isolation of a novel calcium-binding peptide from wheat germ protein hydrolysates and the prediction for its mechanism of combination. Food Chem. 2018;239:416–426. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.06.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59.Wu W, et al. Preparation process optimization of pig bone collagen peptide-calcium chelate using response surface methodology and its structural characterization and stability analysis. Food Chem. 2019;284:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.01.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60.Zhao L, et al. Isolation and identification of a whey protein-sourced calcium-binding tripeptide Tyr-Asp-Thr. Int. Dairy J. 2015;40:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2014.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

61.Shankar KMS, Raizada P, Jain R. A randomized open-label clinical study comparing the efficacy, safety, and bioavailability of calcium lysinate with calcium carbonate and calcium citrate malate in osteopenia patients. J. Orthop. Case Rep. 2018;8:15–19. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62.Guo L, et al. Food protein-derived chelating peptides: Biofunctional ingredients for dietary mineral bioavailability enhancement. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2014;37:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2014.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

63.Liu FR, Wang L, Wang R, Chen ZX. Calcium-binding capacity of wheat germ protein hydrolysate and characterization of peptide–calcium complex. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:7537–7544. doi: 10.1021/jf401868z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64.Zhao L, Huang S, Cai X, Hong J, Wang S. A specific peptide with calcium chelating capacity isolated from whey protein hydrolysate. J. Funct. Foods. 2014;10:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

65.Hou H, et al. A novel calcium-binding peptide from antarctic krill protein hydrolysates and identification of binding sites of calcium–peptide complex. Food Chem. 2018;243:389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.09.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66.Sun N, Jin Z, Li D, Yin H, Lin S. An exploration of the calcium-binding mode of egg white peptide, Asp-His-Thr-Lys-Glu, and in vitro calcium absorption studies of peptide-calcium complex. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017;65:9782–9789. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b03705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67.Kim SK, Jung WK. Beneficial effect of teleost fish bone peptide as calcium supplements for bone mineralization. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2012;65:287–295. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416003-3.00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68.Peng Z, Hou H, Zhang K, Li B. Effect of calcium-binding peptide from pacific cod (Gadus Macrocephalus) bone on calcium bioavailability in rats. Food Chem. 2017;221:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69.Jung WK, Lee BJ, Kim SK. Fish-bone peptide increases calcium solubility and bioavailability in ovariectomised rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2006;95:124–128. doi: 10.1079/BJN20051615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70.Lin J, Cai X, Tang M, Wang S. Preparation and evaluation of the chelating nanocomposite fabricated with marine algae Schizochytrium sp. protein hydrolysate and calcium. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015;63:9704–9714. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71.Guo H, Hong Z, Yi R. Core-shell collagen peptide chelated calcium/calcium alginate nanoparticles from fish scales for calcium supplementation. J. Food Sci. 2015;80:N1595–N1601. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72.Bae YJ, et al. Magnesium supplementation through seaweed calcium extract rather than synthetic magnesium oxide improves femur bone mineral density and strength in ovariectomized rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011;144:992–1002. doi: 10.1007/s12011-011-9073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73.Hirota Y, Sugisaki T. Effects of the coral calcium as an inhibitory substance against colon cancer and its metastasis in the lungs. Nutr. Res. 2000;20:1557–1567. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5317(00)00240-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

74.Ripamonti U, Crooks J, Khoali L, Roden L. The induction of bone formation by coral-derived calcium carbonate/hydroxyapatite constructs. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1428–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75.Mader J, et al. Calcium spirulan derived from spirulina platensis inhibits herpes simplex virus 1 attachment to human keratinocytes and protects against herpes labialis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016;137:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76.Hou C, et al. Coral calcium hydride prevents hepatic steatosis in high fat diet-induced obese rats: A potent mitochondrial nutrient and phase II enzyme inducer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016;103:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77.Ueda Y, Kojima T, Oikawa T. Hippocampal gene network analysis suggests that coral calcium hydride may reduce accelerated senescence in mice. Nutr. Res. 2011;31:863–872. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78.Ueda Y, Nakajima A, Oikawa T. Hydrogen-related enhancement of in vivo antioxidant ability in the brain of rats fed coral calcium hydride. Neurochem. Res. 2010;35:1510–1515. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79.Jung SJ, et al. Bactericidal effect of calcium oxide (scallop-shell powder) against pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm on quail egg shell, stainless steel, plastic, and rubber. J. Food Sci. 2017;82:1682–1687. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.13753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80.Chen Y, et al. Inhibition of 4NQO-induced oral carcinogenesis by dietary oyster shell calcium. Integr. Cancer. Ther. 2016;15:96–101. doi: 10.1177/1534735415596572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81.Terzioglu P, Ogut H, Kalemtas A. Natural calcium phosphates from fish bones and their potential biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2018;91:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82.Shen Y, et al. Engineering scaffolds integrated with calcium sulfate and oyster shell for enhanced bone tissue regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2014;6:12177–12188. doi: 10.1021/am501448t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83.Naga SM, El-Maghraby HF, Mahmoud EM, Talaat MS, Ibrhim AM. Preparation and characterization of highly porous ceramic scaffolds based on thermally treated fish bone. Ceram. Int. 2015;41:15010–15016. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2015.08.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

84.Rocha JHG, et al. Scaffolds for bone restoration from cuttlefish. Bone. 2005;37:850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85.Bramhe S, Kim TN, Balakrishnan A, Chu MC. Conversion from biowaste venerupis clam shells to hydroxyapatite nanowires. Mater. Lett. 2014;135:195–198. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2014.07.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

86.Brennan O, Stenson B, Widaa A, O Gorman DM, O Brien FJ. Incorporation of the natural marine multi-mineral dietary supplement aquamin enhances osteogenesis and improves the mechanical properties of a collagen-based bone graft substitute. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2015;47:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87.Shi P, et al. Characterization of natural hydroxyapatite originated from fish bone and its biocompatibility with osteoblasts. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2018;90:706–712. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88.Dai L, et al. Calcium-rich biochar from crab shell: An unexpected super adsorbent for dye removal. Bioresour. Technol. 2018;267:510–516. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.07.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89.Dai L, et al. Calcium-rich biochar from the pyrolysis of crab shell for phosphorus removal. J. Environ. Manag. 2017;198:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90.You W, et al. Functionalized calcium silicate nanofibers with hierarchical structure derived from oyster shells and their application in heavy metal ions removal. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016;18:15564–15573. doi: 10.1039/C6CP01199C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91.Piccirillo C, et al. Hydroxyapatite-based materials of marine origin: A bioactivity and sintering study. Mat. Sci. Eng. C. 2015;51:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92.Teixeira CMA, et al. Effect of preparation and processing conditions on UV absorbing properties of hydroxyapatite-Fe2O3 sunscreen. Mat. Sci. Eng. C. 2017;71:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93.Zhu Z, Lanier T, Farkas B, Li B. Transglutaminase and high pressure effects on heat-induced gelation of alaska pollock (Theragra Chalcogramma) surimi. J. Food Eng. 2014;131:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.01.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

94.Choi JS, Lee HJ, Jin SK, Lee HJ, Choi YI. Effect of oyster shell calcium powder on the quality of restructured pork ham. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014;34:372–377. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2014.34.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95.Jun JY, et al. Effects of crab shell extract as a coagulant on the textural and sensorial properties of tofu (soybean curd) Food Sci. Nutr. 2019;7:547–553. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

發表留言